Can speed alone be classed as dangerous driving?

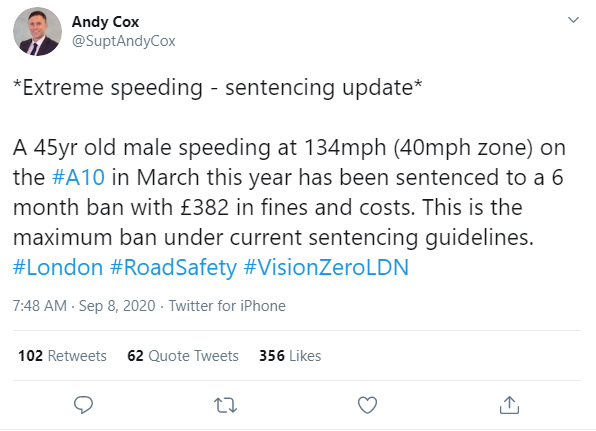

Detective Superintendent Andy Cox inadvertently sparked a mini debate on Twitter about whether somebody driving at excessively high speed can be guilty of dangerous driving when he tweeted:

We don’t know which part of the A10 this offence occurred on, nor the time of day it happened or the road conditions prevailing at the time but I am sure we can all imagine a fairly typical A road through a residential area, as much of the A10 is in London. I suspect that there are not many people who would view 134mph in a 40mph zone as being anything other than dangerous, so the question then is why was this person not charged with dangerous driving?

A road safety group called Vision Zero London provided one possible answer:

“Charging standards dictate that for a single instance of speeding then excess speed is the appropriate offence. On most occasions the driver hits the brakes a second or two after they are clocked, giving no evidence of anything other than speed.”

However, that is not correct for two reasons. First, the Crown Prosecution Service publish the charging standards on their website and they specifically list, “speed, which is particularly inappropriate for the prevailing road or traffic conditions” as an example that is likely to be characterised as dangerous driving.

The other reason that the Vision Zero London response is wrong is because the law clearly allows driving at high speed to be treated as dangerous driving. Their mistake is understandable though given the police’s routine decisions not to treat such high speeds as dangerous driving and the general opinion – perhaps created by Parliament’s decision to abolish the offence of driving at a speed dangerous to the public – that a single incident of speeding can never be sufficient for dangerous driving no matter the circumstances. Let’s take a look at the law.

Dangerous driving is defined as driving in a way that falls far below the standard expected of a competent and careful driver. To win a trial, the prosecution must also prove that it would have been obvious to a competent and careful driver that the defendant’s driving would have been dangerous. That second part is there to prevent people being convicted of driving that is only dangerous in hindsight.

In terms of speeding, it’s not difficult to see a jury deciding that somebody driving at nearly 100mph about the speed limit is dangerous. It’s also not hard to imagine the same jury deciding that the danger would have been obvious to a competent and careful driver, but this is the blog of a law firm so we need to think about the law not just our imaginations.

In Trippick v Orr, Mr Trippick was caught driving at 114mph on a dual-carriageway subject to a 70mph limit. The Sheriff – for this was a Scottish case – convicted him of dangerous driving. The Sheriff accepted that the only dangerous part of the driving was the speed but found that there were potential hazards on the road, such as vehicles joining the road at the junctions, unexpected debris on the road and so. On appeal, the High Court held that the Sheriff had been correct to convict Mr Trippick as potential dangerous ought to be taken into account, although the relevance of any particular factor would vary depending on the particular case before the court.

In the case of McQueen v Buchanan, the Scottish High Court again said that driving at grossly excessive speed might itself give rise to obvious risks that satisfy the test for dangerous driving. This theme was returned to in Howdle v O’Connor where Mr O’Connor was seen by police driving at 119mph on a motorway. It was accepted that the motorway was often subject to hazards such as debris and animals wandering onto the road, although no hazards appeared on the day Mr O’Connor was caught. Mr O’Connor was acquitted by the Sheriff of dangerous driving and the prosecution appealed. On appeal, the High Court found that too much weight had been given to the failure to materialise of any hazards aside from some ten other cars that Mr O’Connor passed as he drove along the motorway. The court said that:

“We accept, of course, that excessive speed alone is not a basis for convicting of dangerous driving... Nonetheless where, as here, the speed is grossly excessive and the car is driven at that speed on a stretch of road with other cars, especially when their drivers would not readily anticipate the speed of the offending vehicle, the proper conclusion to draw is that the driving was indeed dangerous in terms of the section.”

So far, we have looked entirely at Scottish cases for good reason. The law on dangerous driving in Scotland mirrors that in England and Wales and the judgments of the Scottish courts hold persuasive authority over the lower courts of England and Wales where dangerous driving trials would be held. Now though we can look at DPP v Milton, an English case heard in the Queens Bench Division of the English High Court. Lady Justice Hallett reviewed the Scottish cases we have looked at and made several findings. Mr Milton was a highly skilled advanced police driver who had been given a new vehicle and told to test it. He drove at very high speeds on both the motorway and in urban areas. He was acquitted at trial in the magistrates’ court, but the prosecution appealed citing errors in law by the district judge.

First, Hallett, L.J. found that driving at an average motorway speed of 149mph and an average speed of 91mph in a 30mph limit was prima facie evidence of dangerous driving. She held that other road users would have had no warning of Mr Milton coming across their path and would have been taken completely by surprise leaving no margin for error on Mr Milton’s part. It’s worth noting that Hallett, L.J. also pointed out the, hopefully obvious, point that the circumstances that are relevant to dangerousness at speed on an empty motorway are likely to be different to those that are relevant in an urban area.

Secondly, she made clear that while speed alone is not sufficient to found a conviction for dangerous driving it will be sufficient where the context makes that speed dangerous. Her reasoning is clear:

“I decline to find, as Mr Lawson invited me to do, that if an accused drives at speeds twice the limit allowed, he must be convicted as a matter of law of dangerous driving. That would mean that any driver of an emergency vehicle, driving at twice the speed limit, whatever the road conditions, however much warning was given to other road users, would be guilty of dangerous driving per se. That cannot be right.”

So, now we’ve looked at the law we can say a couple of things. We know that speed alone cannot result in a dangerous driving conviction; however, excessive speed in a context where there is at least the potential for hazards to emerge will be sufficient for dangerous driving.

Turning back to the tweet that prompted this point, looking at that we cannot say whether the driver should have been charged with dangerous driving. We can say that if he were driving at almost 100mph above the speed limit on a road where he might encounter hazards then that would be sufficient to convict.

When you are defending any criminal allegation having a lawyer who understands the points the prosecution must prove is key to crafting your defence. If you have been accused of dangerous driving, or any other motoring offence, and would like high quality professional legal advice from a solicitor who really understands the law then call London Drink Driving Solicitor today on 020 8242 4440 or visit our contact page.